Kidney and ureteric stones (urolithiasis) are common — many patients will encounter renal colic or kidney stones at some point in their life. Stones range from tiny, symptomless crystals to large, complex “staghorn” calculi that occupy much of the kidney’s collecting system. Some stones pass without intervention; others must be treated promptly to prevent obstruction, […]

Kidney and ureteric stones (urolithiasis) are common — many patients will encounter renal colic or kidney stones at some point in their life. Stones range from tiny, symptomless crystals to large, complex “staghorn” calculi that occupy much of the kidney’s collecting system. Some stones pass without intervention; others must be treated promptly to prevent obstruction, infection, or permanent loss of kidney function.

This guide explains how location, size, and associated infection determine management, why emergency action is sometimes needed, and how modern minimally invasive surgery — including advanced approaches for staghorn stones — achieves complete removal with short hospital stays and rapid recovery.

Kidney Stones vs Ureteric Stones: The Practical Difference

| Feature | Kidney Stone | Ureteric Stone |

| Location | Kidney | Ureter |

| Pain | Often mild, intermittent | Severe, colicky |

| Risk of obstruction | Low | High |

| Risk of infection | Low | High if obstructed |

| Likely to pass naturally | Yes, if small | Less likely if >5–6 mm |

Why location matters: a stone in the kidney may cause few symptoms, whereas the same stone lodged in the ureter often causes renal colic — severe, intermittent pain caused by ureteral spasm as the stone tries to move. If a stone obstructs urine flow, pressure builds in the kidney (hydronephrosis) and the kidney’s ability to recover becomes time-sensitive.

How Kidney Colic Presents — what clinicians and patients should expect

Acute renal colic is a familiar emergency-room presentation. The pain often begins in the flank and progresses through phases — starting as a dull ache that becomes increasingly severe and then fluctuates in intensity as the stone moves and the ureter spasms. Nausea and vomiting commonly accompany the pain. Visible or microscopic blood in the urine is frequent.

Crucially, the presence of pyuria, fever, leukocytosis or bacteriuria (signs of infection) in a patient with obstruction changes the situation from painful to potentially life-threatening. An obstructed, infected kidney can rapidly progress to sepsis and septic shock; these patients require urgent decompression of the collecting system and critical care support if unstable.

Time matters: renal recovery declines the longer obstruction persists. Brief obstruction (under one week) carries a good chance of full recovery; after several weeks of unresolved obstruction, the likelihood of meaningful recovery falls substantially. That is why prompt diagnosis, accurate assessment, and early urological input are essential.

Symptoms that mandate urgent assessment

Seek urgent specialist evaluation when symptoms include:

If infection is suspected together with obstruction, this is a urological emergency: the priority is to relieve the obstruction immediately to prevent septic shock and the need for intensive care.

Which stones will pass — and which will not?

Several practical factors determine whether a stone is likely to pass without surgery:

Before deciding on treatment, it is essential to know the stone’s size, shape, orientation, radiodensity and exact location — this imaging information guides whether observation, medical management, ureteroscopy, PCNL or laparoscopic removal is appropriate.

Conservative (non-surgical) management

When conditions are favourable, conservative measures may be recommended:

Medical expulsive therapy should only be used in carefully selected cases where spontaneous passage is genuinely likely and there is no infection, significant obstruction, or renal impairment.

When surgery becomes necessary

Surgery is recommended when any of the following are present:

Untreated obstruction and infection risk irreversible renal damage; the window for recovery narrows with time.

Minimally invasive treatment options and expected recovery

Current urological practice favours minimally invasive procedures that achieve high stone clearance rates with little downtime and short hospital stays:

Ureteroscopy and laser lithotripsy

A flexible or rigid ureteroscope is passed through the urethra and bladder into the ureter to visualise and laser-fragment stones. Fragments may be removed or left to pass. This approach has high success for most ureteric stones, requires no external incision, and patients typically have a short recovery and brief hospital stay.

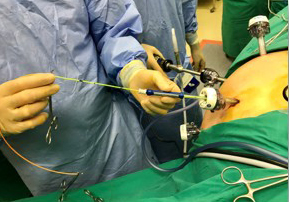

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

PCNL is indicated for large renal stones or complex stone burdens. A small flank tract is created to access the kidney directly and extract large fragments. Modern PCNL techniques achieve excellent clearance rates with limited hospital stay compared with traditional open surgery.

Laparoscopic stone removal

Reserved for impacted stones in difficult anatomical situations or when ureteroscopy/PCNL are unsuitable. Laparoscopy can be highly effective in selected patients, providing thorough removal with minimal external trauma and quick recovery.

The goal of these approaches is consistent: safe, complete stone removal, early mobilisation, short hospital stay and rapid return to normal activity — while maximising the rate of stone clearance.

Staghorn Stones — what they are and how we treat them

What is a staghorn stone?

A staghorn stone is a large, branching calculus that occupies multiple calyces and the renal pelvis. These stones commonly coexist with infection and carry a high risk of progressive renal destruction if not completely removed. Partial treatment or drainage alone leaves residual stone that perpetuates infection and renal decline.

Why staghorn stones require definitive removal

Because of their size and branching nature, staghorn stones are unlikely to pass and are poorly managed by simple fragmentation alone. Complete surgical clearance is the accepted management to prevent ongoing infection and preserve kidney function.

Modern minimally invasive management of staghorn stones

Staghorn stones require specialised surgical planning and advanced operative skill.

Dr Conradie is one of the very few surgeons in South Africa who performs complete staghorn stone clearance using a laparoscopic surgical approach.

Her expertise includes:

Specialised Instruments Commissioned by Dr Conradie

To optimise outcomes for complex stone cases, Dr Conradie commissioned and designed her own specialised surgical instruments tailored for laparoscopic stone surgery.

These instruments allow:

This level of customisation is exceptionally rare and speaks to her depth of expertise in advanced stone management.

Why specialist urological care matters

Effective stone management requires precise assessment of imaging, stone size and composition, renal function, and infection risk. A specialist urologist ensures:

Dr MC Conradie’s extensive clinical experience is complemented by her scholarly contributions, including her published work on renal colic triage and emergency management in the Smith’s Textbook of Endourology (3rd Edition). Her research-informed approach ensures patients receive timely, safe, and highly effective treatment tailored to their individual needs.

Prevention and follow-up — the metabolic approach

Preventing recurrence is a core part of stone care, particularly for patients with recurrent stones or complex disease. A metabolic evaluation is recommended when stones recur or when large/complex stones are present. This may include:

Lifestyle advice — adequate hydration, moderated salt and animal-protein intake, and tailored dietary modifications — complements medical therapy.

Regular imaging (ultrasound or low-dose CT as indicated) and specialist follow-up reduce the risk of unnoticed recurrence and allow early intervention if new stones develop.

Conclusion

Stones span a spectrum from asymptomatic kidney crystals to infected, obstructing, or branching staghorn calculi that threaten renal function. Management must be individualised: small, uncomplicated stones may pass with medical support; obstructing or infected stones require urgent specialist management; large or complex stones demand definitive surgical clearance.

Modern minimally invasive surgery offers high stone-clearance rates with limited downtime and short hospital stays. Dr MC Conradie’s advanced clinical expertise in managing complex stone disease — including complete staghorn stone removal using tailored surgical strategies and specialised instruments — ensures patients receive timely, effective care designed to remove stones completely and preserve kidney health. If you have persistent flank pain, haematuria, recurrent urinary infections, or imaging that shows stones or hydronephrosis, seek prompt specialist evaluation. Early assessment and the right intervention make the difference between full recovery and preventable loss of kidney function.